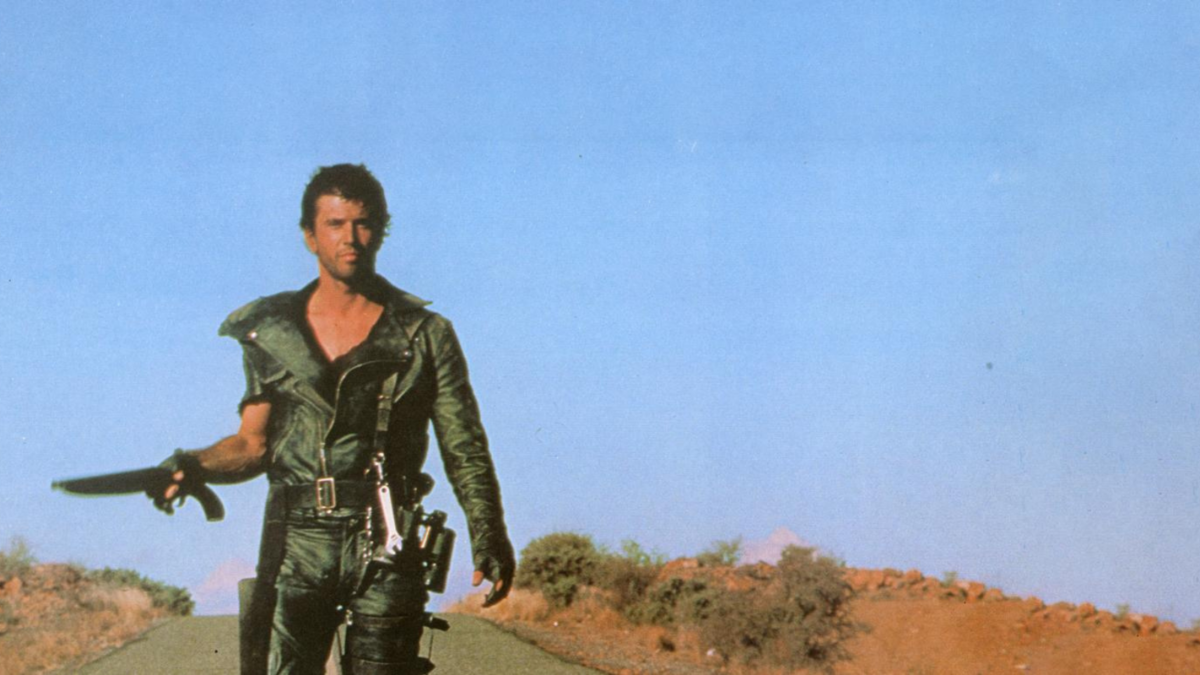

More than Mad Max for new film fund

“One of the things that concerned me as a member of the screen industry in Australia was how we were going to hang on to this great growth we saw during Covid, where we got increased production and much greater awareness,” says Greg Basser, the former CEO of Village Roadshow and one of the founders of Australian Entertainment Partners (AEP). “We always wanted to make things in Australia, because we’re proud of it and wanted to give back to an industry that had given a lot to us. But it always came down to the dollars.”

At Village Roadshow Basser produced projects including Joker, Mad Max: Fury Road, Gran Torino, and Where The Wild Things Are (which didn’t make a lot of money, Basser admits, but was made in Melbourne, and so benefited the local economy). Later, Basser founded AEP alongside Bob Osher and David Burdge; its new Screen Fund, distributed by Damien McIntyre’s GSFM, is intended to act as a funding source for local productions as well as international productions filmed in Australia.

It’s aimed at family offices, high net worth individuals and the odd institution; Basser and Co. want to raise $100 million in equity to pair with a $500 million debt facility from the “lead banks” of the film industry. It will be a seven-year fund (five years with a two-year wind down) with a cap of 40 original productions, increasing to 55 total projects with sequels and continuing series included, and Basser estimates that it will produce $1.7 billion of content – the “vast majority” of which will be spent in Australia. It’s targeting a 15-20 per cent return, and a boost to the local film industry.

“I left Village and started thinking about why our industry couldn’t be like the UK, where they introduced incentives and the business went like that,” Basser says. “There was never any infrastructure that would finance film or TV made in Australia. There are some lenders – a great company called Fulcrum that finances against rebates and incentives – but I watched really good Australian productions never do as well outside Australia as they should have because they never had the funding that allowed them to be put together in a way that would get them access to the best distribution platforms.”

The Australian financial services industry has a long history with entertainment. Media Super used to provide debt financing for film production, while TWUSuper even invested in stage plays. And back in the day Bankers Trust financed several of the early Kennedy Miller Mitchell productions through 10BA, which allowed investors to claim a 150 per cent tax concession and pay tax on only 50 per cent of the income earned from their investment. That built an “enormous industry” of tax-effective investing before the government reduced the concession out of concern for its growing cost.

“They didn’t really have rules about proper producers, proper production, finishing it, delivering it, showing it – it was just ‘you invest and this is what you get’,” Basser says. “The schemes were marketed with a minimum return. That was just financial engineering to give high net worth individuals further income. And there were funds done in the past that assisted in raising finance for television productions that, in my view, were designed to help the sponsor satisfy some regulatory obligations but left the balance of the risk with the investors. That didn’t go well.”

Basser says the fund will take advantage of the “huge change in the (entertainment) industry” brought on by streaming content; 10 years ago, US buyers of new content spent around US$30 billion. Last year, Basser estimates it was US$154 billion, with most of it bought by streamers on a cost plus basis where syndication doesn’t figure. The AEP projects will be covered by “contracts and government rebates and incentives concurrent with the commencement of production”.

“You can’t say there’s no risk but our risk is different,” Basser says. “There’s no risk in rebates and incentives because the Federal offsets are all legislated and the State incentives are all grants. You have an agreement you can sue them on, but the Australian government always pays. The risk is that your buyer doesn’t pay.”

“But they’re in the content business, and the last thing they don’t pay for is their content. You’re talking about Disney, Netflix, and Apple… If Sony decided not pay – and I’ve never seen any of these studios not pay – suddenly they’re in real difficulty because it’s not that they’re not paying us – they’re not paying the leading banks in the industry.

“The risk goes from audience acceptance or the commercial viability of the project to sovereign risk on 35-40 per cent of the obligation and investment grade risk on the balance – it’s receivables. It’s like a property development fund that doesn’t break ground until it has a commitment to buy the building for a fixed margin.”