Farmland: Are super funds missing out on a tasty investment morsel?

Australian agricultural land has rarely been on the menu of the large APRA-regulated super funds, with the consensus being this asset is simply too risky due to fluctuating commodity prices and exchange rates, as well as the climatic vagaries that can bring devastating droughts, floods and bushfires.

But if they are reluctant to dig deeply to invest in this asset class, the same cannot be said of their overseas brethren who have exhibited a keen appetite for farmland assets (of which more later).

Jim McKay, managing director of Warakirri, an Australian multi-boutique asset management firm offering a diversified agricultural fund, says: “Australian institutional investors have historically shown a limited appetite for agricultural assets.

“Aside from factors such as volatility around climate variability and commodity prices, there’s also a lack of liquidity, an understanding of the operational complexity of managing farmland assets and ESG risks. In addition, agriculture is also excluded from performance benchmarking tests.”

John Coombe, executive director of the asset consultancy JANA, says farmland can be “tough” for institutional investors because getting a return on investor capital is challenging.

“It’s always been difficult because you’ve got to buy a lot (to make it worthwhile) and with the price of land it’s really difficult to make it add up,” he tells Investor Strategy News, adding the return is typically in the sale of the asset instead of an ongoing income stream.

“It’s not that some funds wouldn’t like to do it – and some funds have done it like the $93 billion REST Super with Warakirri. It’s just getting the scale given how big these funds are now.

“There’s also the question of classification – does it fit in a property or alternatives basket, for example – which matters when it comes to determining how it might meet APRA’s performance testing,” he says.

Sam Sicilia, chief investment officer at the $115 billion industry fund Hostplus, concurs with Coombe in saying it’s difficult to scale investment in farmland.

“There’s also the issue of the managing the asset, climate, and commodity price fluctuations. When you compare it with an airport investment, for example, where you know exactly what you are getting – especially exclusivity – then it’s harder to make the case for farmland.”

He says Hostplus did run the ruler over the Northern Australian Pastoral Co in 2016 – its 80 per cent owned by QIC, the Queensland Government’s investment arm, with the remaining 20 per cent with Tasmania’s Foster family – but decided not to proceed. “Farmland is always a possibility, but we’re certainly not actively looking.”

While McKay notes the conservative approach to farmland investment, he adds that this negative sentiment could be changing.

“They can see the clear benefits of the low correlation of this asset class to traditional asset classes and understand the compelling investment returns that can be achieved across the agricultural landscape. There’s also the potential upside of enhancing environmental outcomes as part of their broader ESG objectives,” he says.

That’s a sentiment that would sit comfortably with REST that explains there’s a social dimension to its investment in Warakirri Cropping. [The $34 billion Queensland-based Brighter Super also dabbles in agricultural assets.]

“By 2050, it’s estimated that the world will need to produce up to 54 per cent more food, feed and biofuels than in 2012 to feed a projected global population of 9.7 billion people.

“Current farming as we know it is unlikely to meet that demand. Instead, agriculture of the future will need to be more sustainable by producing more from less, and that’s where we believe Warakirri Cropping comes in.”

Those super funds that have taken the plunge with this asset could hardly complain about the returns, as highlighted by the 2025 Bendigo Bank Agribusiness report, Australian Farmland Values.

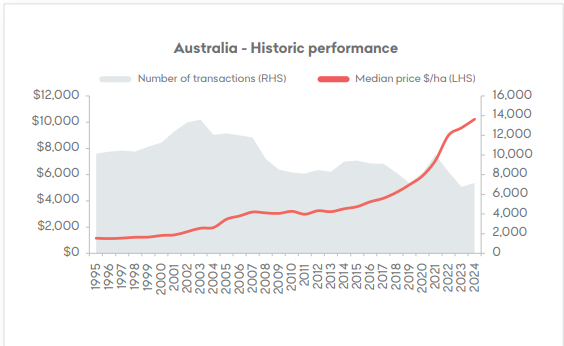

In calendar 2024, the national median price per hectare of farmland increased 6.9 per cent to a record $10,231 per hectare (see graph). The report says: “While this was the 11th consecutive year of growth, it represents a notable cooling in the rate of annual increases compared with 2018-22 when median price growth of Australian farmland more than doubled.”

But it’s longer term where farmland has delivered. “The national median price has tripled across the past decade, rising by 201 per cent at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.6 per cent,” the report says. Over a longer time horizon, the national median price has a 20-year CAGR of 8.6 per cent.”

Certainly those numbers are proving tempting for overseas investors. In January, New Forests, a global investment manager of nature-based real assets and natural capital strategies, closed its Australia New Zealand Landscapes and Forestry Fund, raising about $600 million from institutional investors from Europe and Asia-Pacific, including three new investors, Evli, an investment management business spanning Finland and Sweden, Kyushu Electric Power, a Japanese energy company, and a German insurer.

A year earlier, the same fund had its first close, raising $450 million, with the investors including the Swedish pension fund Andra AP-fonden and the German pension group Bayerische Versorgungskammer.

In 2023, the Canadian pension fund, the Alberta Investment Management Corp, in partnership with the Australian and New Zealand-based investment manager, New Agriculture, put down $300 million to acquire the Kimberley Cattle Portfolio in Western Australia. Situated in the state’s northeast, the portfolio consists of seven pastoral leases covering 1.8 million hectares, five sub-leases covering nearly one million hectares and an agistment agreement over about 150,000 hectares.

The HSBC Global Research report, The Future of Food, noted that in 2023 about 10 per cent of the world’s population went hungry. With the global population likely to add nearly another billion people over the next two decades and incomes rising, total food consumption will likely rise by more than 50 per cent, and possibly by 70 per cent, by 2050. Clearly, it’s this long-term outlook for food demand that has overseas investors hungry for Australian farmland. The question is, will the locals join the party?