From the Bible to Wry & Dry: musings of a wealth manager

When Anthony Starkins was retrenched for the second time within a few months in 1998, after nearly 20 years in investment banking, he decided he should seek financial advice. His ensuing frustrations resulted in the business to which he has devoted the last 20-plus years, First Samuel Limited.

“I spoke to financial planners, banks, brokers and accountants about what to do with my redundancies and I couldn’t find anyone who seemed to know how to competently and honestly handle the money,” he says. “I thought that there must be other people like me… who need advice, who need someone to look after the investments and do all the administration.”

Starkins’ career in investment banking spanned London, Tokyo, Singapore, Sydney and his Melbourne home, mostly at Schroders and J.P Morgan. He says he was “absurdly paid” but worked “absurdly hard”. No doubt he could have continued on that path if he so chose, but he didn’t.

The term “wealth management” was only just starting to gain common industry usage at the time. Sure, there were organisations that performed all three functions, from the old life offices, banks and brokers to the big retail fund managers, but the functions weren’t integrated. Neither were those organisations well equipped to handle the inherent conflicts between advice and investment management (that is, conflicted remuneration, such as commissions). One wonders whether a royal commission into their administration would reveal similar murky secrets, beyond charging dead people for life insurance.

In the day, at the height of the dot-com boom, it was only a handful of smaller independents that offered their clients separately managed accounts, let alone truly discretionary managed accounts. It was still a world dominated by managed funds and traditional planner distribution.

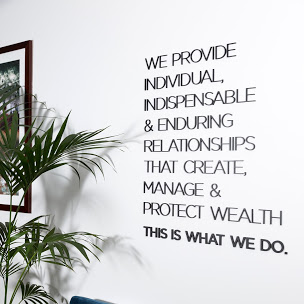

A good way to describe First Samuel can be found in large capital letters on the wall of the firm’s reception area in its modern but-unassuming offices on Collins Street, Melbourne. While Starkins is fond of borrowing quotes from others, including historical quotes and biblical ones, these words are his own:

First Samuel, established in 1999, has about 260 clients with a total of $520 million under management. Starkins reckons he would know 200 of those clients “reasonably well” and 100 of them “very well”. It was one of the first holders of a managed discretionary accounts license.

The firm has 21 staff, including Starkins, and a board of four non-executives, plus himself as executive director. He still controls the majority of shares in the wholly staff-owned non-listed public company. The firm’s chief executive is Sean Cash and the CIO Craig Shepherd.

Guy Strapp, the chairman, joined the board in only 2019 . He has a long line of fund manager credits, including chief executive and before that CIO of the $270 billion Asian-based Eastspring Investments (formerly Prudential Asset Management), and senior investment and management roles with Citi, BT Financial Group and J.P. Morgan. He is also chairman of Platinum Asset Management.

The other non-executive directors are: Murray Baird, a lawyer and academic; John Bryson, a former director and shareholder of J.B. Were; and Claudia Häger, a CFA who is the head of operations at Tennis Victoria and has had a career in investment management and international sports leadership.

Starting an investment business at the height of the dot-com boom was not easy for a group of investors with a fundamental stock-picking style, with a value tilt and focus on long-term wealth creation. Some value-orientated Australian managers, such as Hambros Hopkins, closed down, and others, such as Rothschild Australia Asset Management, sold up (to Westpac).

This was weathered, as were the 2008 global financial crisis and the worst of the covid-19 impact last year. It was during the financial crisis that Starkins decided to indulge his literary side and demonstrates an appreciation for irreverence. He started to write his weekly ‘Wry & Dry’ column, which became attached to the firm’s client investments update. The column, he says, seems to have developed a mind of its own. It has certainly proved popular.

Clients, as well as finance journalists, would agree with him when he says: “Most investment and economics newsletters are so boring.” Wry & Dry is not. Even the footnotes, which should be renamed in this case, have a quirkiness to them which prompts the reader to wonder about their relevance.

He has elicited the aid of renowned cartoonist Patrick Cook, now in semi-retirement, as illustrator. Cook has drawn for the Australian Financial Review as well as numerous other publications. This example (below) accompanies Starkins’ take on the recent European Super League breakaway debacle, which was to be backed by J.P. Morgan with the active involvement of Jamie Dimon, its Chair and CEO.

In the lead item, published April 23, Starkins writes: “Wry & Dry now invites readers to review the words of Jamie Dimon, J.P. Morgan’s Chairman and CEO [1], in the bank’s recent Annual Report: “As you know, we have long championed the essential role of banking in a community – its potential for bringing people together, for enabling companies and individuals to reach for their dreams.” Lovely stuff, positioning the bank in a socially responsible world. And focussing on communities. Wry & Dry teared up.”

He finished it off with this quote from the original John Pierpont Morgan, and a couple of must-read footnotes: “The insurrection against the European Super League was really an insurrection against elites. Mr Dimon has shown that he sits in the elite grandstand. And that he has forgotten the words of John Pierpont Morgan, the founder of the bank, “A man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.” [2] Did he really trust those wealthy soccer elites? Or perhaps just the fees he would earn?”

The footnotes:

“[1] The fact that the Chairman is also CEO, as is the case in most American companies, tells another story.

“[2] J.P. Morgan dominated corporate finance on Wall Street in the late 19th and early 20th century. During the Panic of 1907, he organised a coalition of financiers that saved the American monetary system from collapse. J.P. Morgan and Co begat: Morgan Guaranty Trust, Morgan Stanley and Morgan Grenfell. Wry & Dry can disclose that he worked for J.P. Morgan Investment for 10 years.”

At its annual investor ‘CIO Dinner’ last month (April) First Samuel put the latest market collapse and rebound into perspective, from a comfortable position of strong outperformance. For the year to March, the firm’s main portfolio strategy, targetting CPI plus 3.5 per cent a year return, averaged 28 per cent for clients after fees, putting it inside the top ten out of 838 comparable “balanced” funds in the Morningstar universe, whose average return was approximately 14 per cent.

Nevertheless, Starkins can see the headwinds. Valuations ex-resources and ex-banks are still near all-time highs. For the ASX, this is a P:E of 24x compared with the long-term mean of 16x. The peak was 26x late last year. The big-tech-heavy S&P 500’s dispersion remains wider. “It’s a good time to hold some cash,” Starkins says. The question is “how much?’.

At the CIO Dinner, First Samuel identified nine “milestones”, with the cash quandary a reflection of the uncertainties ahead. Addressing these is at the heart of its current portfolio construction. They are:

- Macro trends: is the market expensive?

- How much cash? The average Aussie equities’ portfolio has a little over 15 per cent in cash, which has been inching up since last November.

- Interest rates: have collapsed, with direct impacts on gold positioning.

- Bonds: avoid fixed interest securities?

- Inflation: “I hear a train coming.”

- Net zero: a battery-led solution? How to pick key investment themes within the theme.

- President Biden’s infrastructure policy: how will it impact Australian companies.

- Working from home: winners and losers.

- Change is inevitable: “Change provides the value equities are destined to provide.”

The cash quandary is, in part, a question for individuals. First Samuel believes that many investors hold, mistakenly, “too much cash”. Only a few years ago investors received a risk-free return, now they get return-free risk. They haven’t adjusted. Starkins says they should intentionally decide: (a) how much they leave for a “true rainy day”; (b) how much needs to be producing a regular income and; c) how to protect their purchasing power from inflation.

Starkins spends up to eight hours writing each week’s Wry & Dry. It has become an important part of the firm’s and his own communications with clients and other stakeholders. Offering up more than just his views on investments; it gives at least a glimpse of the mark of the man, his broader values and beliefs.

He admits to being a “small ‘l’ liberal” with a streak of curiosity. He believes that many of First Samuel’s clients are similarly curious about the workings of the world, according to his column’s feedback and one-on-one discussions. He likes to give politicians in particular a new name. Victorian Premier Dan Andrews, for instance, is ‘Chairman Dan’. Here’s part of a commentary on the Victorian Belt and Road Initiative which was dumped by the Federal Government:

“Readers would have read that last week the federal government gave Chairman Dan’s Belt and Road Initiative the DCM. No tears were shed, not even by the acting Victorian Chairman and members of the ministry (cabinet was not consulted on the original BRI idea). It was serendipitous that Chairman Dan was still recovering from his inexplicable accident, and didn’t have to front the media to provide a retrospective justification for his Belt and Road Initiative initiative. Everyone (bar one) was wishing that the Victorian BRI coffin could be buried, unnoticed and unloved.”

Starkins, a man of faith, is an avid reader of history. He also knows his Old Testament. First Samuel, the wealth management company, was named after one of his favourite chapters, the first book of Samuel, which deals with Israel’s political evolution to a monarchy, eventually led by King David.

In this, Samuel speaks for the Lord when he says: “Those who honour me, I will honour, but those who despise me will be disdained” (1 Samuel, 2:30). Samuel, a prophet and seer, is known as the “last of the judges”. He comes out of it all looking pretty good.

If any of his negative opinions of people and their behaviours could be labelled ‘disdain’, Starkins is too polite to let on. But it’s fair to say he is not too fond of some of the consequences of the industry’s regulatory system. Growing up in suburban Melbourne his family had a healthy distrust of big business and bureaucracies, which has stayed with him.

More formally he says: “First Samuel is very supportive of measures that improve the transparency and the quality of advice provided to clients. It is noted, however, that at times clients have responded that the level of rigour being applied has become burdensome upon them…

“In addition to this, there has also been the challenge of advice businesses facing different oversight bodies with differing expectations. Financial service licensees that provide financial product advice currently are accountable to ASIC, AFCA and the TPB, whilst their representatives (and indirectly the licensee) to FASEA. Additionally, the Royal Commission had concluded that another oversight body for the discipline of financial advisers was necessary.”

Those two redundancies in 1998 may have cemented the distrust of big business, certainly in financial services. The first was from J.P. Morgan Investment where he worked for 10 years, culminating in the position of regional head of marketing for Asia Pacific, based in Singapore.

Under the J.P Morgan entry on his Linkedin page he has an acerbic line: “In 1998, devised a Hong Kong/China entry strategy that was ignored because ‘there was no future in China’.”

The second was from the old Norwich Union where he tried to resurrect the ailing investment arm. This was to no avail. He was made redundant and the firm was acquired by Portfolio Partners. He hasn’t bothered his Linkedin profile with the inclusion of his two months at Norwich.

Job security is not the reason anyone starts up his or her own business. It is a range of less quantifiable comforts that control offers, such as the sense of freedom to pursue both personal and professional goals. This can be through writing a wry and dry column for curious investors or developing a new China/Hong Kong entry strategy for the next generation of wealth managers.

Meantime, Starkins, 67, is still enjoying the business too much to contemplate retirement. “My wife said to me that she married me for breakfast and dinner, not for lunch,” he says.

He has no desire to retire.