Hamsters, monkeys, and market crashes

Two case studies this week provide an interesting opportunity to re-examine investor behaviour. As it turns out, a monkey can beat the market.

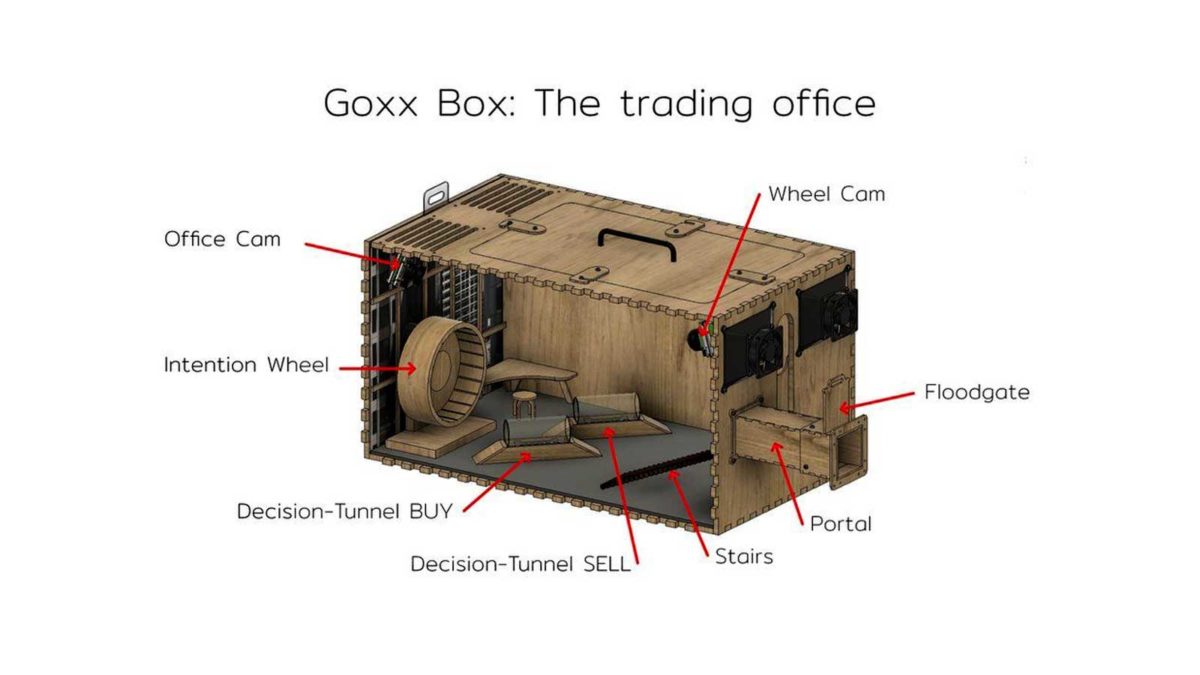

Have you heard the one about the crypto-trading hamster? Mr Goxx is the only employee/inhabitant of Goxx Capital, a specially outfitted cage which allows him to trade cryptocurrencies based on his movements through an exercise wheel and two tunnels. He’s currently outperforming the broader market by about 20 per cent (past performance is no indicator of future returns – speak to a financial adviser before investing with Goxx Capital).

It’s not the first time such an experiment has been done. Indeed, animal investors are almost as common as their human counterparts – and often outperform them. Take for example Orlando the Cat, who selected stocks by dropping his favourite toy mouse on a grid of numbers and beat a team of professional investors, or the famous case of Raven Thorogood III, a chimpanzee that managed a whopping 365.4 per cent return by throwing darts at a random group of tech stocks in 2000.

Aside from an opportunity to take a swipe at the supposed masters of the stock universe, it’s usually unclear what, if anything, we’re supposed to take away from these experiments. Proponents of passive investing believe it demonstrates that humans are just bad at active management, while some believe it’s a sign that markets truly are efficient – dud companies go bust before the animals ever a chance to pick them. That said, Raven was completely wiped out in the Tech Wreck; maybe markets aren’t as efficient as we think. One conclusion could be that when animals can pick the winners, we’re in trouble.

Experiments such as these tend also to reflect the broad dynamics of the market at the time they’re conducted; in an environment where it mostly goes up, you can probably pick a lot of winners at random (especially when they go up as explosively as they did before the Tech Wreck). So fret not, value investors; Raven’s performance doesn’t necessarily mean the end of the bottom up investment process.

An interesting corollary from these animal experiments is a new study from MIT that found humans are (surprise) bad at timing the market. But more interestingly, those who considered themselves to have “good or excellent” investing experience and knowledge were more prone to panic selling than those who considered themselves so-so. Those who fit into the generally monied classes of “owner” or “executive” – were also more likely to panic sell.

The study analysed brokerage data from 2003 to 2015 and is retail focused, meaning there are obviously some considerations to make about the data. Male investors aged 45 or older, who were married or divorced, and who had dependents, were more likely to panic sell. That group might be starting to think more seriously about preserving capital for retirement or other lifecycle events, and the shortened timeframe in which they can make up for any loss. But while the researchers found that panic selling did function as a stop-loss measure by protecting capital during a crisis, panic sellers tended to miss the subsequent rally and the profits that came with it. They also liquidated the majority of their portfolio, without consideration to assets that had historically outperformed.

Contrast all of this with the experience of the animal stock pickers. Mr Goxx, despite trading one of the most volatile assets in the market today, doesn’t seem all that worried. So perhaps there is something to be learned from the animal experiments: Don’t panic.