Smaller industry funds putting the spotlight on member service

While some large profit-to-member funds are dragging the chain on member service, other smaller funds – less than $50 billion in assets under management – with a more defined industry focus have made a strategic decision to publicly mandate their member service offering.

The Queensland building industry fund BUSSQ, the non-government schools NGS Super and First Super, which evolved from the furniture and joinery, pulp and paper and timber industries, are three funds that have developed and published the service standards their members can not only expect but demand.

For Natalie Previtera (pictured), chief executive of NGS Super – it has about 120,000 members and $16.2 billion in assets under management – drawing a line in the sand about member service was not a “come to Jesus moment”.

“Member service has always been part of our DNA. Whether we were required to do it or not, we’ve always been on the ground in the schools because we know how that really positively impacts on member outcomes.

“What does this mean in practice? We look at our complaints data and how quickly we can resolve an issue; phone calls and emails – how quick the response; member sentiment surveys; exit surveys; and how many members are converting from accumulation to retirement accounts.”

Bill Watson, chief executive of First Super – it has more than 70,000 members and about $7 billion in assets under management – did have a Jesus moment. It was March 2020 and the COVID pandemic was leaving a trail of destruction through financial markets.

In his blunt assessment, service dropped off the table – the unintended consequence of the focus on returns and fees.

“People just couldn’t get through to their funds. We even had people from other funds ringing us. It’s that old saying – what gets measured matters. And service didn’t matter, so it wasn’t measured.

“So we developed the concept of a member service promise where funds should be compelled to publicly set out their service standards, including answering the phone, emails, processing claims and the like.”

Since 2013, the MySuper product dashboard has required trustees to provide members with information on returns, risks and fees and costs. But Watson argues the dashboard lacks a critical element – member service.

“It’s up to each fund to work out what they want to promise. So, you can have a fund saying we’re going to be cheapest fund in Christendom. The only way you can contact us is via social media.

“That’s okay, if that’s what they want to do, because people can still make an informed decision. That’s the first step. Then it’s imperative that funds report periodically, and the way to do that is via the APRA heat map. What I’m essentially saying is that you have a three-legged stool – performance, costs and service – and each fund must decide how its structured.”

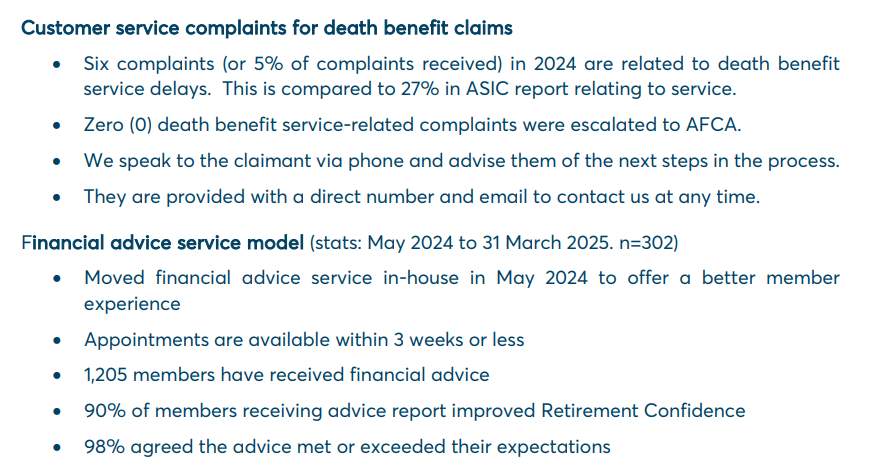

BUSSQ Service Statistics

Watson says members typically have an “oh sh** do I have enough moment” around 50 years of age – a view Previtera shares.

“Our average member is a 47-year-old female, so they’re that pre-retirement cohort,” she says. “It’s at that age where they start to think and act about retirement with our role being to do everything possible to ensure they’ll have a comfortable retirement.”

Damian Wills, chief executive officer of BUSSQ – it has more than 70,000 members and about $7 billion in assets under management – says its member service promise, launched in 2024, focusses on the type of service members need.

“We’ve introduced a level of transparency by publishing our performance on our website as we want to be accountable and focussed on our commitment to deliver a high level of service for members,” he says.

“The metrics include insurance service levels, call-centre service, getting out and about on our members’ worksites and financial advice. We believe that members should be able to easily speak to a real person, that we’ll take the time to understand their individual needs, have the knowledge to help them and resolve their inquiry quickly.”

He says there’s been an absolute focus on returns and fees, yet it doesn’t cost a “sheep station” to properly service members.

“It’s important to remember that if members aren’t happy, they won’t stick with you just because your returns are great. That’s what we’re seeing in the ASIC report about insurance claims where service, in some instances, has been terrible at the very time people are most vulnerable.”

While conceding BUSSQ has higher fees, he contends that getting the service right so members can have a better retirement is a price they’re prepared to pay.

Wills is on the same page as Watson in arguing the profit-for-member funds will pay a high price if they don’t address member service.

“We’re a highly regulated industry now, but if we don’t get this right then it will get a legislative response, irrespective of who’s in government. It could even reach the point where funds lose their licences,” Wills says.

For Watson, the most immediate consequence of poor service – and the media attention it attracts – is the loss of social licence.

“We’ve carved out a space about us being the good guys, the ‘compare the pair’ campaign that’s been so successful. This will be at risk.”

He adds that the outgoing Financial Services Minister, Stephen Jones, was aware of the issue and had done a good job using the ministerial bully pulpit to get funds focussing on delivering and being accountable for servicing members.

“But he’s had the problem of bringing the industry along. As we know from experience with the performance test, there’s always going to be heaps of arguments about how it’s measured, what should be measured and the like. To be frank, I think parts of our sector are using that to frustrate change.

“There’s a bunch of funds who would prefer that service, personal service, isn’t measured because of decisions they’ve made about resource allocation, about who they’ve engaged as administrators and where they are with technology transformation.”