Why quants have the edge in China A-Shares

As China’s domestic market liberalises and regulatory upheaval eases, quant strategies stand to gain that will gain from the massive inefficiencies in its “opaque landscape.”

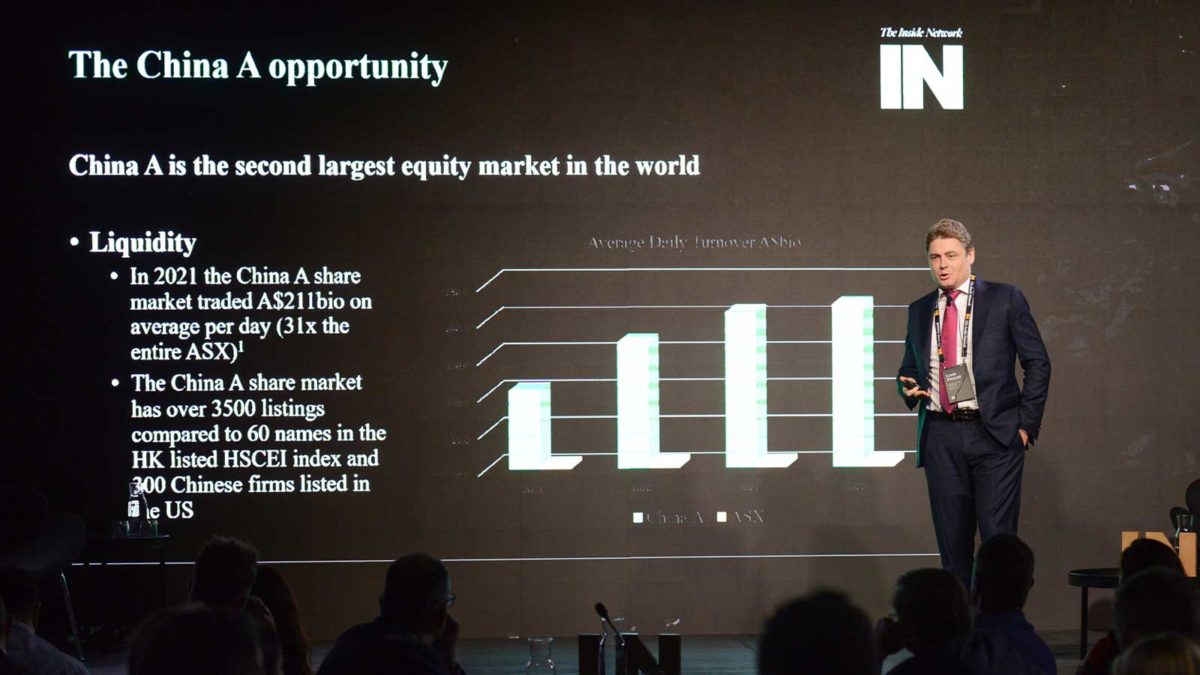

While many bottom-up investors tout the domestic consumption story as the main reason for getting involved in China A-Shares, its huge, retail-dominated market also makes it perfect for a “nimble, liquid, and arguably more efficient” quant strategy.

“Despite being so large, it’s still really inefficient. Most of the major brokers only cover a hundred to two hundred stocks,” Lewis Prescott, quant manager Mingshi’s international head, told the Inside Network’s Alternatives Symposium on Wednesday (February 23). “It’s really not covered well in the traditional sense that we would consider a market efficient and the pricing and instruments that we would consider are efficient in price discovery.

“68 per cent of the China A-Share market has less than three analysts, and 33 per cent has no coverage at all. There is opportunity here in meaningful size.”

The domestic China A-Share market, which has around 3500 listings, is also dominated by retail investors – 70 per cent of daily trading in the domestic market is essentially dumb money. Their motivations are “extremely different” to retail and institutional investors in the US and Australian markets, which makes the market “inefficient, but predictable.”

“If you want a comparison, if you look at the US to see where it had over 70 per cent retail trading, you have to go back to the 1950s,” Prescott said. “So it’s an extremely unique phenomenon in a large equity market.”

But there’s also higher trading costs and limited hedging tools, and single stock shorting inventory is also in short supply – meaning a high barrier to entry for global investors that typically dominate the space. Quant strategies, which are often characterised by hundreds of smaller, more liquid positions, have also been a boon through the period of intense regulatory upheaval that other strategies have struggled to navigate. A feather in Mingshi’s cap is the fact that during the upheaval, its strategy (along with those of a handful of other managers) was up substantially.

“The regulatory overhang in China is massive… but the geopolitical headlines, and what you’ll read on the front page, are very far away from what’s happening on the ground in respect of the China Securities Regulatory Commission and market liberalisation,” Prescott said.

“Since the 2015 correction in the China A-shares market, China has become more liberal, reducing quotas for access, there’s more access for offshore investors, more single stock shorting availability, a friendlier attitude to the alternatives space generally.”

But it’s still an “opaque landscape” and has historically lacked trusted managers for offshore investors. Prescott noted that – for whatever reason – the onshore domestic market has steered away from co-mingled funds, and any major onshore manager will “easily” have more than a hundred funds trading alongside each other.

“When they come marketing in Australia, they’ll usually show you one fund,” Prescott said. “It’s likely their smallest fund and their best performing fund as well. Ask them for their largest, worst-performing fund and start the conversation from there.”

Mingshi launched its Australia office last year, headed up by Michael Negline, and is in the process of launching two unit trusts for Australian investors.