To play for the ‘volcano’, one must be early: Ruffer

As I look out of the window into the Walled Garden at Auckland, I can see the stooped body of the Prime Minister weeding one of the vegetable patches – there must be an election in the offing, and this must be a photo opportunity.

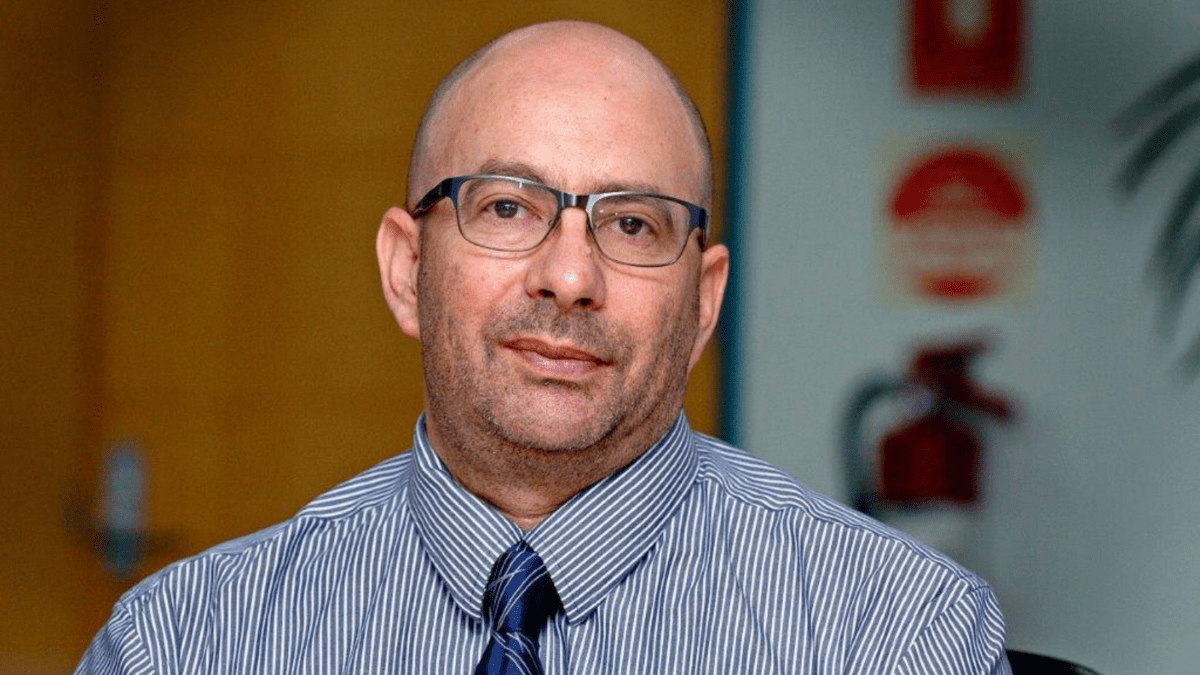

But the sentries at the investment gate are not best occupied in taking opportunities to be photographed – eternal vigilance is the uncomfortable adjunct to those responsible for other people’s money. As I write this, I am aware that we have fallen well short of our investment objectives over the last eighteen months. The days of delivering on our investment aims – and some – in 2022, when the market fell 18 per cent, are a faraway country.

Our investment strategy is based on a simple premise: we take genuine risk, and we seek, on a one year rolling basis, not to lose money. In our near three decade existence we have delivered solidly on the aims we strive for, and our clients expect. For a year and a half, the risks we have taken have cost clients money, so that raises two questions, interlinked: have we got it wrong, and have we lost the plot? It goes without saying that the arithmetic shows we did get it wrong, so perhaps the more acute question is: is Ruffer as a house right to persist in seeing gremlins in the woodshed, when there are so many easy ways of benefitting from the opportunities presented in risk markets?

Uncomfortable as it is, we are holding steady with the views we have. My personal view is, of course, only a singleton’s, but to my mind the probability of a setback – a really decent one – is likely, and likely not too distant either. The trouble, of course, being that ‘not distant’ is not like the moment when the boiled egg stops being runny. It’s more like an Iceland volcano erupting – a wait of two years for such an event is as a ship in the night to mother nature. To get absolutely right the timing of these cataclysms is to get lucky; if one is going to play for the volcano (as one absolutely must, if it’s a likelihood), one has to be early. If early, there is a real possibility of being uncomfortably early, and for many ‘uncomfortable’ and ‘unacceptable’ are too closely intertwined for comfort. Many investors, sympathetic to the idea that the markets have become unanchored, will nevertheless keep one straw in the punchbowl so as not to look ‘absolutely’ wrong, and the equivocation of ‘not yet’ looks like prudence until it isn’t, in the way that being uninsured gives you more cash in the pocket, until the Gainsborough is nicked.

Our core assets are the key to this philosophy. Events in Japan hold a big clue to future outcomes. The yen is the school chump who is always good for a tease. Tokyo’s bond yields, although moving higher, are still below Western yields, which have also been firming as the possibility of falling interest rates there recedes. Meanwhile, to quote Molesworth, ‘any fule kno’ that if you borrow in yen, you get to pay a low interest rate, and when you come to close off the deal, you’ve made a tidy profit on a yen that is even weaker than when you bought it. As I write this, the yen-dollar rate is 159: where might it go? When the Molesworths are crowded on one side of the ship, there’s a strong possibility, confirmed in the present case by the fundamentals, that the market will turn.

For a long while, the Japanese enjoyed, rather than endured, the fall in their currency. But they don’t like the inflation it brings, nor the excess of tourists. The newspapers proclaim in banner headlines the yen-dollar rate: ‘what a fine mess you’ve got us into here’ is the moan at government inaction. The key to the investment opportunity in anticipating a stronger yen is that there are two groups of investors short of it who appear not to have perceived the embedded risk to their assets. One is Japanese institutional investors, long of US and European government bonds, who hold them in dollars and euros, and the other is non-Japanese borrowers in yen, yen which is sold to fund the carry trade. This currency trade should move explosively when it goes, as there will then be a big number of forced buyers of the yen. In investment terms, that means the Japanese currency can appreciate far, far above reasonable value. Finger in air, it might move by exactly double that – the overshoot being the same as today’s undershoot. We anticipate that the portfolio would more than make up for prior disappointment in such an instance. Is this a prediction? Directionally, yes it is. I know I want to be long of the yen.

We could say the same for credit spreads, which have concertinaed into a tight premium over government bonds. Why has this happened? It’s because, now interest rates are high and inflation is still acting like a half-trained puppy, no extravagant yield premium over government bonds is necessary. That will change – pretty much for sure – but high fixed interest yields make it very expensive for bears to trade on the short side, since ‘short investment-grade bonds’ means having to pay a high rate of interest on the borrowed bonds acquired for shorting. Timing costs money, as well as taxing patience. There is a similar story for volatility trades. But their attraction – aaah, their attraction! – the more the market falls, the better they do.

In the old days, we had bull markets, and bear markets – the fluctuations were like the waves of the sea, causing the water level to rise a bit at the top of the bull wave, and then fall a bit, as the impulse gave way to a bear phase. Will it be like that this time round? I doubt it. We have had a 40 year bull market, during which there have been only the briefest of conventional bear phases – 1990-1992, 2000-2002, 2008-2009, 2022 – all too short for ennui to set in. Instead there have been stock market crashes – crevasses which, in a jiffy, do immense damage to investment returns. Indeed, the identification of these has been the single biggest contributor to our track record. In each and every one, we were too early – in 2000, it was 14 months, in 2008, it was a full two years, in 2020, it was at least two years, and this time it is 18 months at a minimum. In each case, we had correctly identified the nature of the oncoming crisis, and were able to concentrate investments into the appropriate asset class.

What might the stock market index do in such an eventuality? Henry Maxey’s insight is an interesting one – the question most of us ask is ‘how far could it drop?’ Henry goes to another question, ‘how fast would it drop?’ The answer is, he believes, found in the first of the recent big crashes, that of 1987, which came out of a blue sky – the market in its fifth year of a new generational bull market, and three years away from the next recession. Small stocks had enjoyed a spectacular bull market; when the fall came, it followed a queasy Friday, with the UK market half-closed because of the great storm. On the Monday, the market was marked very sharply down, and held eerily steady until about 11am, when it began to tick down again. By the close it had dropped by 23 per cent. The reason – again, I use Henry’s word – was mechanical, not emotional, although I well remember how much emotion was generated. The flying buttress of protection, portfolio insurance, collapsed almost instantaneously, having turned out to be ineffective, and those with leveraged positions in their portfolios were forced to do whatever they could to cover those trades. That is the situation today: each area of the markets, from the hedge funds trading small differentials with high leverage to staid old Wall Street favourites, hollowed out by the replacement of equity with debt, has no reserve armies to defend losses on the central battlefield. It will happen so quickly that a response from central banks (notably the Federal Reserve, but this is the domain of every central bank from Peru to Portugal) will be powerless to come to the market’s aid in the moment of its crisis. In this environment, we would be disappointed not to make a gain which decently restores the portfolio to where our clients expect returns to be.

That, in a nutshell, is where we are. One or two things we can promise clients. We will not lose our nerve. Secondly, if the facts change, we will change our mind. Thirdly, we will continue to remember that we are not engaging in an intellectual game; we are the custodians of other people’s money.

One last thought. Since I took on the Chair of Ruffer in 2010, there has been a regular enquiry as to when I will hang up my boots. At the risk of causing disappointment, the answer is that I intend to stay at Ruffer until I am a chocolate fireguard.