Why taming the inflation tiger will be harder than the 1970s

Inflation hasn’t been this high in 40 years, but investors have become convinced that central banks can still tamp it down it with relative ease – a conviction reflected in market pricing and which has created “an avalanche-prone financial system” unable to tolerate the higher interest rates the economy now needs.

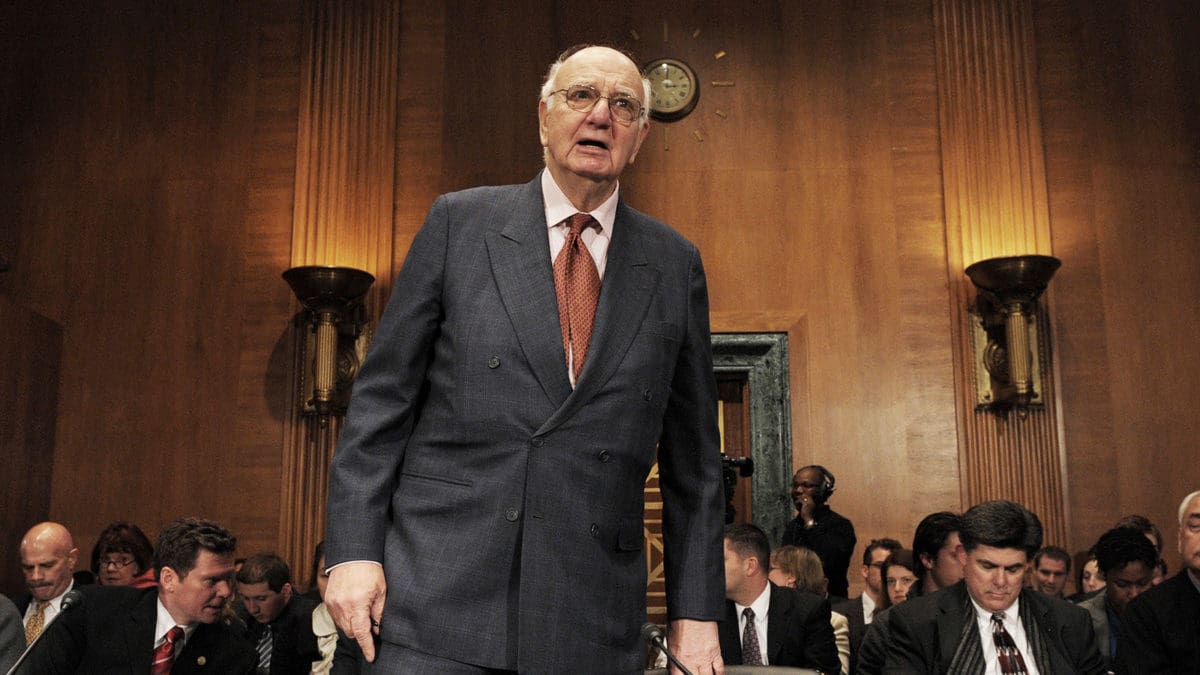

The paradigm markets and economies now find themselves in is similar to that prior to the Volcker Shocks – which saw interest rates rise as high as 20 per cent – with two key differences.

“First, you can only crush inflation when society has gone through the ringer,” said Jamie Dannhauser, economist at Ruffer. “Taming the inflation tiger by 1979 did have broad political support in the United States and in many other countries. It doesn’t today. Unemployment, inequality, uncaring elites – these are the things that shape today’s politics, in much the same way that inflation did when Volcker arrived.”

“Second, it can require a large and very sustained dose of harsh medicine. Politically, the really courageous act of Volcker was keeping interest rates sky-high in 1981 and 1982 as the US plummeted into recession and unemployment shot through 10 per cent. Volcker had learned from the failures of 1960 and the early 1970s.”

The real errors the Fed historically made, to Dannhauser’s mind, were not during the hiking cycle but in the economic downswing, when monetary policy was eased “too soon and too aggressively.” Today, markets are focused on how hawkish the Fed will be in the next 12 months. But what matters more is how it reacts when the next recession emerges – a concern that has leapt to prominence in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but which was looming even before the Covid shock.

High inflation had mostly disappeared from developed markets in the 40 years until today, held at bay by a number of secular, interlinked trends, including China’s economic renaissance; the breakdown of the Soviet Union and ensuing integration of Eastern Europe into the EU supply chain; rapid improvements in digital technology; the surge in female labour force participation; and globalised goods production. All of this was supported by a laissez-faire attitude to international commercial relationships.

But the electorate has turned against globalisation, manifesting in the election of Donald Trump and the vote for Brexit, and “the world’s speed limit has now fallen”. That dynamic has also been reinforced by global energy demand that is now outstripping supply, while supply chain shockwaves have rippled out from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Amplifying these problems is the fact that liquidity has also been a “critical variable” in the new central bank policy regime. In 2018, the Fed “blinked when markets wobbled”, making it clear that the previous regime had been radically reimagined and that the Fed now saw its job as running the economy as hot as possible. Fiscal policy also went to “whatever it takes” settings too, with government debt as a percentage of GDP now back at WWII levels.

“A recessionary bear market is now a very significant risk for all of us,” Dannhauser said. “One has probably already started. The Fed will now have to press harder on the brake than it wanted to, and other central banks that had hoped to delay their own hawkish tilts simply don’t have the luxury anymore.”

“The world’s most important bank is slamming on the brakes hard, at high speed, on a road with poor visibility, that it hasn’t driven in several decades. The odds that the car comes to a halt safely are pretty poor, and this is happening in an economy where demand is more sensitive to asset prices and leverage than it really has ever been.”

But Dannhauser notes that a harsh tightening cycle could also have a massively deflationary impact.

“This apparent paradox makes navigating markets especially tricky,” Dannhauser said. “Is the best way for us to protect clients’ wealth to build defences against an inflationary future, the obvious endgame given the dynamics I’ve just mentioned? Or is in fact the graver threat to portfolios a deflationary lurch in risk assets, because by depressing the brakes far too late, central banks will inevitably stamp on them far too hard.”

But it’s not an “either or” discussion; while Jerome Powell is serious about pushing inflation rates to three per cent this year, and portfolios will certainly need a short-term airbag, the Fed will eventually reach its pain point and begin to loosen policy. Investors will believe that rising unemployment will hold inflation back, and that government bonds will once again protect portfolios. Markets will feel “a bit more conventional”. But that likely won’t last; the temptation to ease will be too great.

“The lesson we must learn from the 1970s and Volcker’s tough medicine soon after is that monetary policy sometimes has to remain tight – even when the economy is in recession. Volcker could do this of course, because electorates had suffered a decade of stagflation beforehand. Arguably, it also required a very high-risk, low-reward gamble that didn’t pay off for (then president) Jimmy Carter.”

“… In all likelihood, economies will enter the next recession with very elevated inflation. My guess is that they’re also going to do so amidst a bigger draw-down in equities than has been the case in recent decades… Central bankers will do what they know, politicians what they think the electorate demands. The mistakes of the late 60s and early 70s will likely be repeated.”