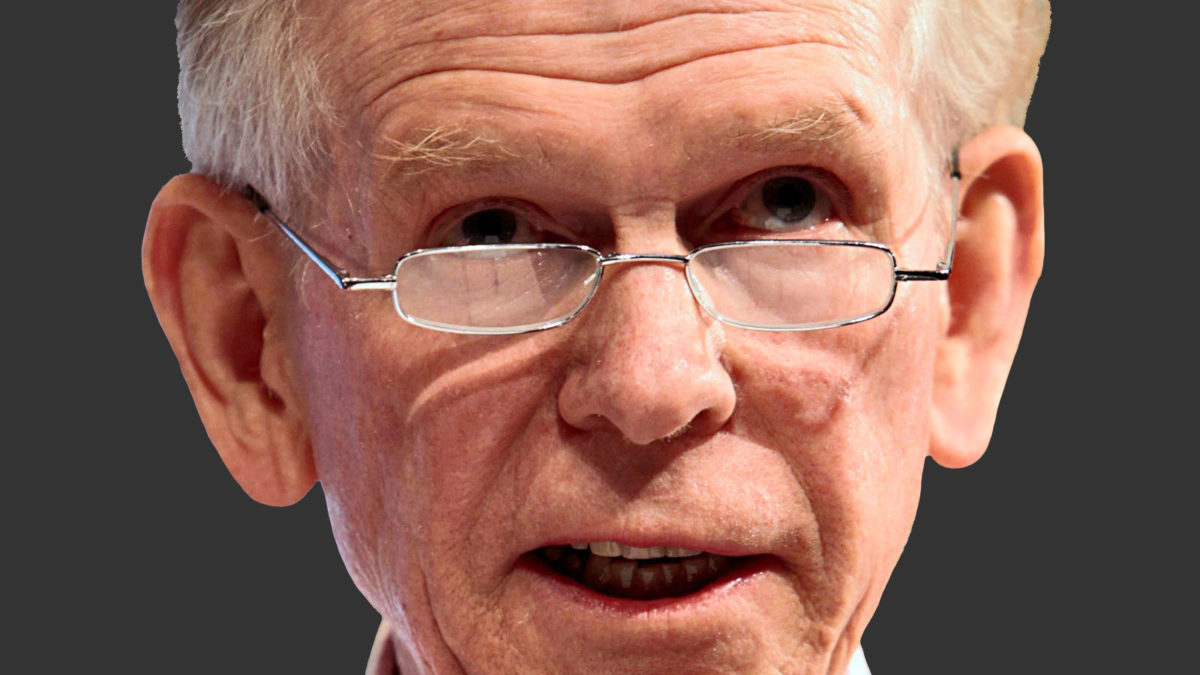

Grantham calls ‘the death of the vampire’

Jeremy Grantham believes the “superbubble” he’s been warning about for years is now on the brink of collapse – and that the “wild rumpus” can begin at any time.

Calling the collapse of a market bubble is anybody’s game. One needs only to know that it exists – something now patently obvious to any investor with a functioning brain – to start predicting that it will pop it. Only a few of those predictions are really worth examining, and even fewer are worth taking seriously. The latest missive from GMO founder Jeremy Grantham, who has made a career of navigating bubbles, is one of those few.

Grantham believes that we’re not just in a bubble, but a “superbubble”. And when it pops – as all bubbles eventually do – the damage will be far worse.

“While it is dangerous to have a bubble in equities – for the loss of value can cause a shock through the wealth effect that can get out of control, which was a part of the problem in 1929 and the ensuing slump – it is much more dangerous to have a bubble in housing, and it is very much more dangerous to have both together,” Grantham wrote in a note titled ‘Let the Wild Rumpus Begin’. “The economic consequences of the double bubble in Japan are arguably still playing out.”

The defining features of the end of any bubble, to Grantham’s mind, are the “crazy investor behaviour” that begins to permeate markets – this time in the form of extraordinary speculation on electric vehicle and meme stocks – and an acceleration in the rate of price advance to two or three times the average speed of the full bull market.

But the final feature of many superbubbles – the true alarm bell – has always been a “sustained narrowing of the market” and sustained underperformance in those speculative stocks, which fall as investors make a flight to what they believe to be safe blue chips.

“A plausible reason for this effect would be that experienced professionals who know that the market is dangerously overpriced yet feel for commercial reasons they must keep dancing prefer at least to dance off the cliff with safer stocks,” Grantham writes. “This is why at the end of the great bubbles it seems as if the confidence termites attack the most speculative and vulnerable first and work their way up, sometimes quite slowly, to the blue chips.”

Grantham lays the blame for this bubble, and other historical cases, squarely at the feet of the Fed and other central banks, criticizing them for a stance that has favoured deregulation and light touch enforcement and for responding to previous bubble collapses with more and more stimulus – “more lifeboats rather than iceberg avoidance.”

“As of today, the U.S. has seen three great asset bubbles in 25 years, far more than normal,” Grantham writes. “I believe this is far from being a run of bad luck, rather this is a direct outcome of the post-Volcker regime of dovish Fed bosses. It is a good time to ask why on Earth the Fed would not only have allowed these events but should have actually encouraged and facilitated them.”

“The fact is they did not “get” asset bubbles, nor do they appear to today. This avoidance of the issue seemed to us remarkable as long ago as the late 1990s. Alan Greenspan, who I considered then and now to be dangerously incompetent, famously acted as cheerleader in the formation of the then greatest equity bubble by far in U.S. history in the late 1990s and we all paid the price as it deflated.”

Grantham has made a career of calling asset bubbles, but might well be breaking from process in calling the end of this one. After all, he’s previously said that it’s near impossible to tell when one will burst and what exactly will burst it. It’s an inexact science, one that has more to do with investor psychology than structural forces. One day, optimism is at its peak and the market reaches an all-time high – and the next day, for some reason, everybody’s just a little bit optimistic.

“We are in what I think of as the vampire phase of the bull market, where you throw everything you have at it: you stab it with Covid, you shoot it with the end of QE and the promise of higher rates, and you poison it with unexpected inflation – which has always killed P/E ratios before, but quite uniquely, not this time yet – and still the creature flies,” Grantham writes.

“(Just as it staggered through the second half of 2007 as its mortgage and other financial wounds increased one by one.) Until, just as you’re beginning to think the thing is completely immortal, it finally, and perhaps a little anticlimactically, keels over and dies. The sooner the better for everyone.”